The Fed’s Inflation Fight and the Markets

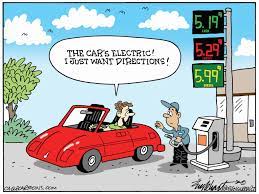

Markets have been troubled. Open any brokerage or 401(K) statement and you are likely to see a page of red. It seems that nearly everything has gone precisely the wrong way: bonds are down, stocks are down, and gas prices (along with the price of nearly everything else we purchase) are up.

Markets have been troubled. Open any brokerage or 401(K) statement and you are likely to see a page of red. It seems that nearly everything has gone precisely the wrong way: bonds are down, stocks are down, and gas prices (along with the price of nearly everything else we purchase) are up.

Fear and uncertainty abound, and the headlines foreshadowing the end of the world are not helping.

And yet…perspective matters.

There are three important points:

- While painful, what has occurred is a healthy and needed reaction to the withdrawal of liquidity.

- I am beginning to find more optimism in our monetary policy than I have in nearly three decades.

- This is not the time to react emotionally. Even if we are pushed into a recession, if history is any indication, we will likely be fine.

With that, let us begin.

Liquidity and monetary policy

As we’ve discussed in previous updates, the U.S. Federal Reserve is the Central Bank to the United States and, as the name states, is essentially the lender of last resort. The Fed (as it is colloquially referred) has very crude tools. It can:

- Signal what it’s going to do by talking.

- Raise and lower the rates at which banks borrow (through one mechanism called the Federal Funds rate).

- Expand its balance sheet by (essentially) printing currency and buying bonds.

For the sake of brevity today, generally speaking, the Fed cuts rates when unemployment is too high and raises rates when inflation is too high (remember the dual mandate).

Yet, for four decades, the Federal Reserve has provided more and more liquidity by steadily lowering rates. And yet, for four decades, growth has been, by and large, strong and unemployment has been, by and large, reasonably low (with some exceptions).

This introduced a strange dynamic where each time the Fed cut rates, it would cut much more deeply than when it would raise rates … hence, rates fell over a long period of time.

This is, in essence, just an expansion of liquidity. If a consumer would want to borrow $10,000 at 5 percent, they would probably be willing to borrow a much higher sum at 3 percent.

More broadly, in the last three years, for example, the Federal Reserve has created (through the Treasury) an additional $5 trillion (yes, trillion) out of thin air to help counteract the economic effects of COVID-19. In 2007/2008, the Fed introduced a bit over $1 trillion to counteract damage from the Global Financial Crisis. To be clear, some of this was absolutely needed and a good deal of it was remarkably effective.

And yet, as with anything, there are no absolute decisions, only tradeoffs. The obvious consequence is we have increased the money supply in the United States and, therefore, the value of our dollars has diminished. This, along with pent-up demand from COVID and supply chain disruptions, caused inflation to rise … and has created a very specific form of inflation referred to as monetary inflation.

As such, once it was clear inflation wasn’t “transitory,” the Fed finally began taking steps to reverse the cycle.

First it signaled it was slowing or stopping the expansion of its balance sheet, then it signaled it was going to raise rates and now it is in the process of raising rates.

As markets (both financial and physical) went up because rates went lower, markets go down when rates go higher. On the margin, the introduction of liquidity makes prices increase and the removal of liquidity makes prices decrease.

This is both logical and, in aggregate, a healthy move to begin focusing more intensely on the real economy and less intensely on the performance of markets.

Market performance during recessions

The question on the minds of many is therefore how far will the Federal Reserve go? Will the Fed bring inflation back down? Yes, I believe so. Will the Fed irreparably crush markets? No, I don’t believe so. Will the Fed push us into a recession? Well, possibly…

Which brings us to Chart 1: market performance during a recession, after a recession, and during “normal” times.

The period following recessions is quite good, however, as markets recover and generally with less of the unhealthy excesses that exacerbated the sell-offs in the first place. These periods are so good, in fact, that over the seven recessions from 1970, the year immediately following the end of the recession were slightly better than “normal times.”

Therefore, what to make of it all and what are investors to do?

- First and foremost, breathe. We have been through inflation, pandemics, wars, poor policies, high rates, low rates, high unemployment, low unemployment, and many other difficult environments before. Incentives drive behaviors and markets are driven by incentives. Those incentives haven’t changed and, as providers of capital, we, as investors, must still rely on those principles above all else.

- Second, recognize our human brain isn’t very good at market timing. Markets are down and if you have experienced the pain thus far, there is very little expected value in trying to time the market going forward. Even the most sophisticated investment organizations in the world can’t time markets very well.

- Third, go back to your plan. Market sell-offs are wonderful opportunities to refresh on goals and objectives. Refresh on how much you are spending and whether savings rates are high enough. Dare I say there might even be opportunities (as most equities are now less expensive and most bonds are now yielding more)?

- Fourth, review your fixed-income (e.g., bond) portfolio. The yield curve is now inverted which means shorter-term bonds are often yielding more than longer term bonds, and those shorter-term bonds are often associated with less risk. There are many other factors involved, of course, but where possible, consider shortening duration (the maturity of the bonds in your portfolio) if you haven’t done so already. Remember, inflation is not yet under control and it is unclear how soon that will happen.

In closing, take a moment to breathe, do not react emotionally, and use the difficult markets as an opportunity to reaffirm your long-term plan.